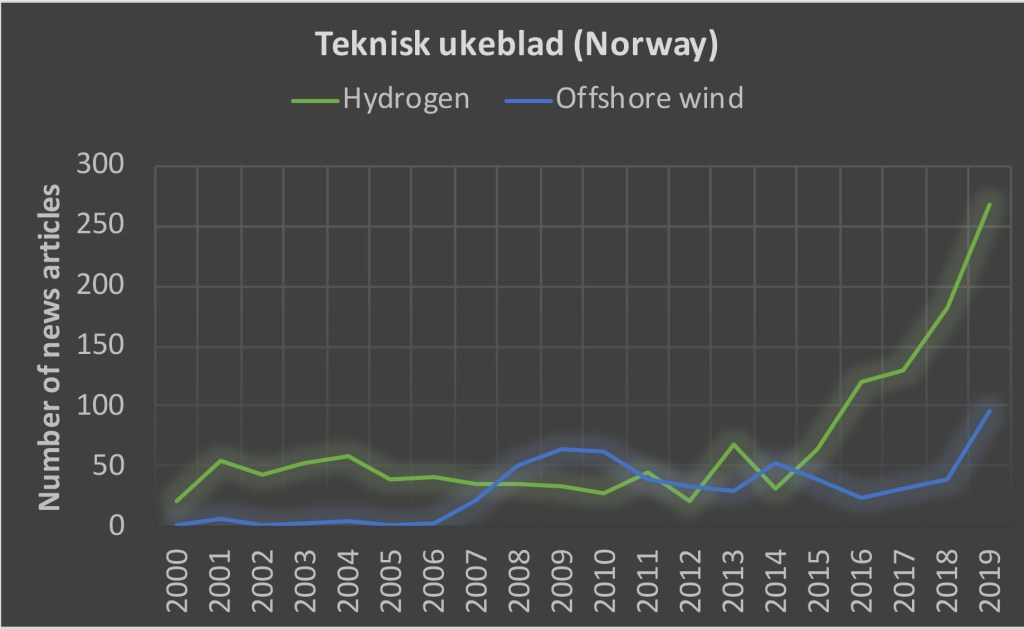

The number of published articles and funded research projects about hydrogen as an alternative energy fuel, seems to experience a growing interest in Norway within the last decade (Figure 1).

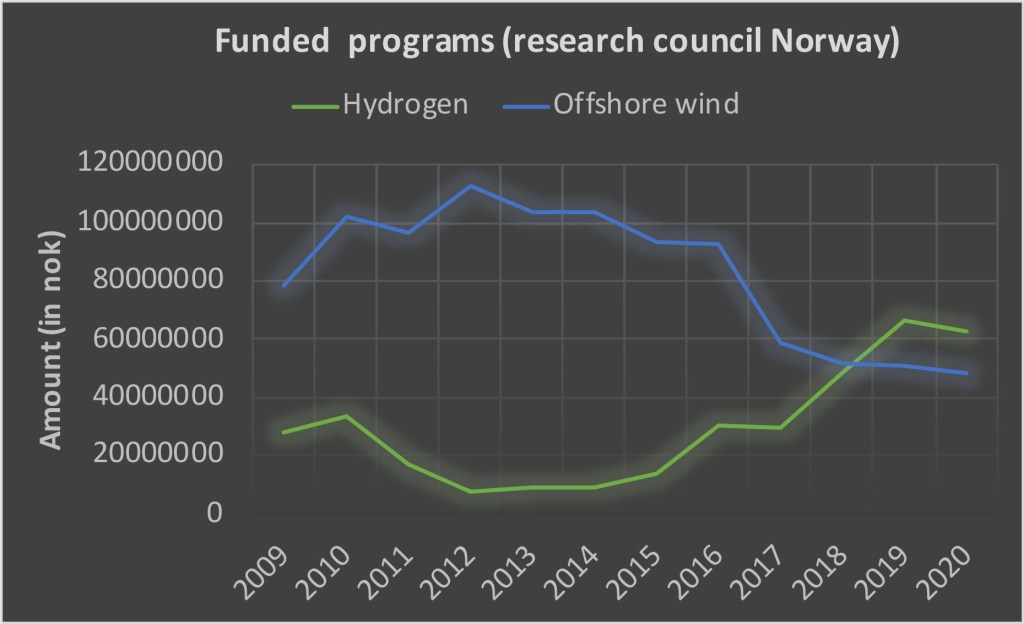

(Right) Granted hydrogen and offshore wind projects. Data retrieved from forskingsrådet.no

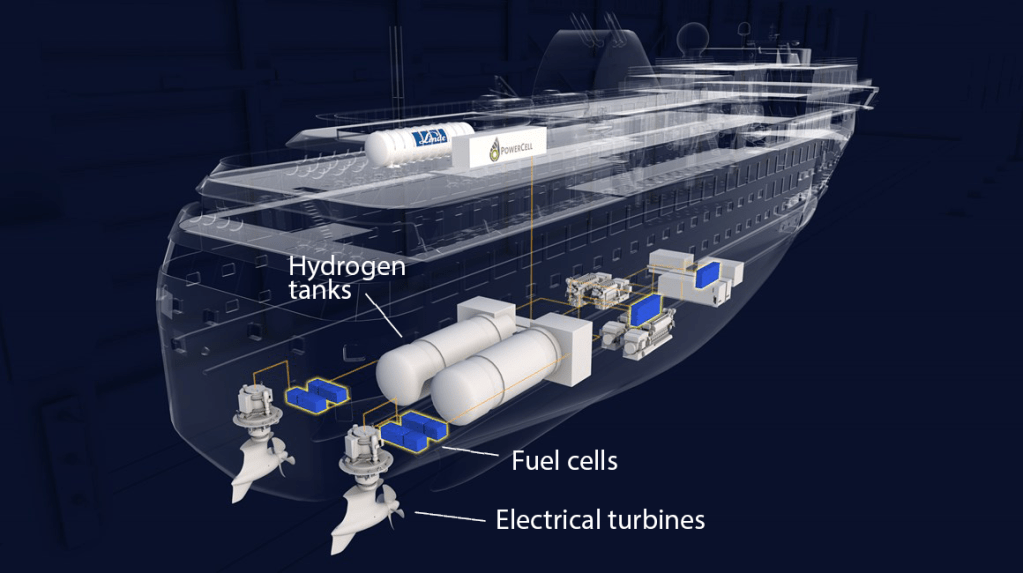

A concrete example of this general trend comes from the Norwegian shipbuilding company, Havyard, announcing a prototype for building a hydrogen-powered vessel [1].

So why is hydrogen gaining popularity, especially in Norway?

Hydrogen can be used as a fuel to produce electricity and move an electrical engine with zero GHG emissions. An additional–and important– advantage is that hydrogen can be stored and can be quickly refueled–improving the notable limitation of charging electrical batteries.

In order to generate electricity from hydrogen, a fuel cell is required. The fuel cell takes advantage of the chemical energy from hydrogen and, together with oxygen–obtained from air–,generates hydrogen ions and electrons which result in the generation of an electrical current that can then be used to produce work [2].

An illustrative example of how a putative hydrogen system would look like can be seen from the Havyard hydrogen-powered ferry model (Figure 2).

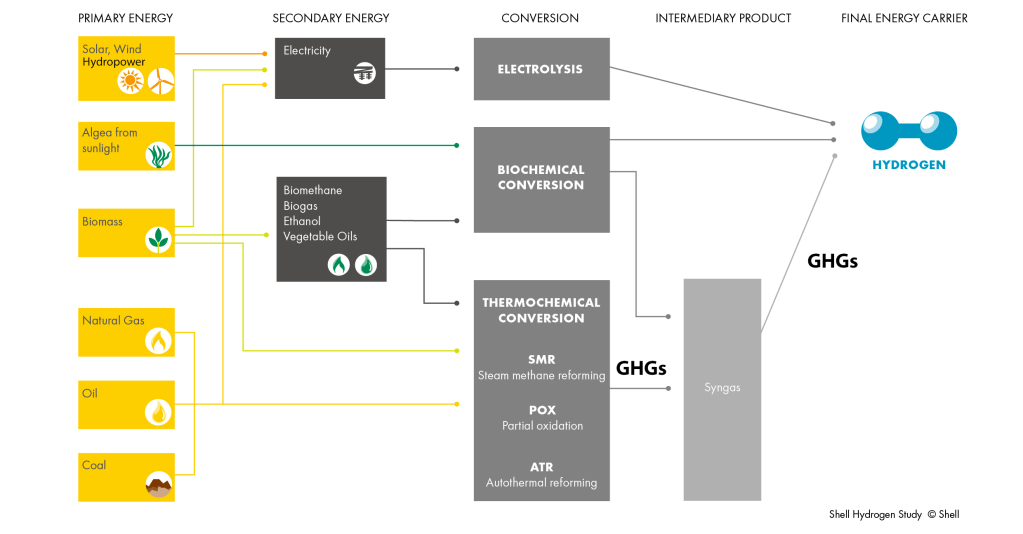

Hydrogen can be produced from several ways (Figure 3), yet the only null-GHG emission production comes from water electrolysis; consisting on splitting the water molecule (H2O) into its hydrogen and oxygen components. This process requires 50 kWh of electrical energy, approximately, to produce 1 kg of hydrogen [3] and it is seen as being a low efficiency process. This is why a famous technology entrepeneur referred to hydrogen as “bullshit” [4], as it is more efficient to directly charge electrical batteries than to use that electricity to produce hydrogen.

Despite Elon Musk’s blunt statement being true for the use of hydrogen in domestic vehicles, it might not be as a disadvantage for the case of maritime transport where electrical batteries are limited for i) its capacity to cover the long-distance trips cargo vessels do and ii) its long recharging times.

An interesting avenue for electricity-generated hydrogen is its coupling to renewable energy generation when there are electricity surpluses. This would be a good way for coping with the intermittent nature of renewables and not wasting electricity when it is not consumed. Surpluses in electricity can be used to produce hydrogen by electrolysis and store it for later use.

Today, however, 90% of hydrogen originates from fossil fuels–being steam reforming of natural gas the largest used method–releasing CO2 into the atmosphere. The CO2 emitted through this process is confined within an industrial framework and potentially easy to capture with the development of new technologies for Carbon Capture and Storage. Therefore, another interesting avenue for clean hydrogen production would be through the coupling of CO2 capture and storage to hydrogen production. The main challenge is to find compatible technologies that both yield high-purity hydrogen and can capture CO2 efficiently and at a reasonable cost [5]–equally important is finding suitable storage mediums for the captured carbon. Today, the main pathway appears to be oil and gas reservoirs [6]. This is already done to increase the reservoir pressure and thereby increasing the yield of oil or gas.

An issue concerning hydrogen is its storage; as hydrogen is a very low-density gas and therefore requires compression and other specialized forms of storage (such as liquefaction) to achieve desired energy densities. This also represents another energy loss to the energy cost of compression.

Hydrogen is also highly flammable; startling examples of the past [7] and others more recent [8] exemplify this intrinsic characteristic. Therefore, care should be taken when designing hydrogen infrastructure.

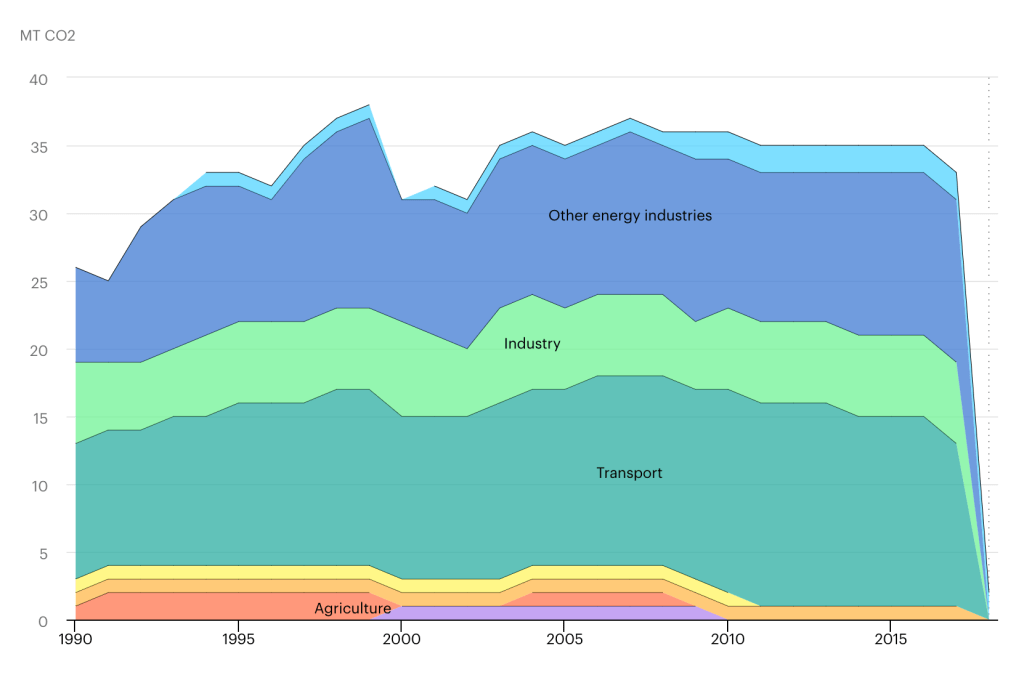

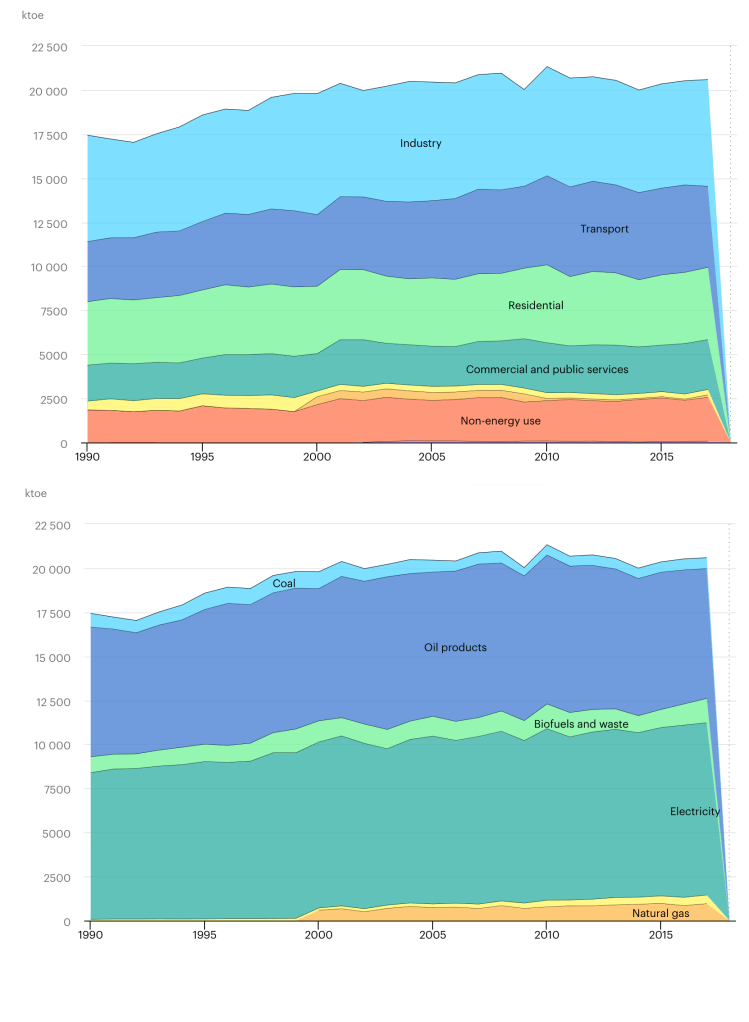

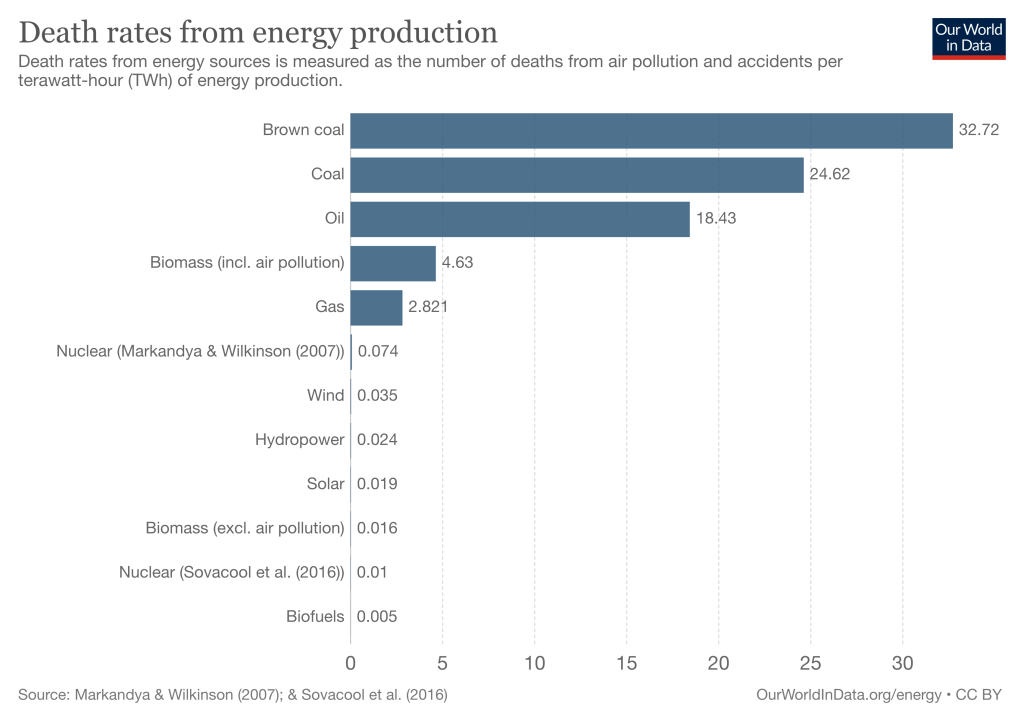

A transition to renewable energies not only concerns peak-oil and climate change but also public-health: fossil fuels (coal and oil, in particular) are the highest sources among deaths by air contamination per TWh of energy produced (Figure 4).

In Norway, the high traffic of diesel-driven ferries cruising the western fjords has resulted in strong local air and water contamination [9].

A shift towards clean energies not only implies an improvement in air quality–as in this example–but in all the elements of the ecosystems we live in; with a direct impact on human health.

Overall, Norway seems, again, to be in the avant-garde of the renewable energy transition; betting heavily for all possible paths towards a more environmental-friendly future.

GLS

[1] Havyard, “https://www.havyard.com/news/2019/prototype-for-hydrogen—one-step-closer/,” 2019.

[2] Wikipedia, “https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fuel_cell,” 2020.

[3] R. Bhandari, C. A. Trudewind, and P. Zapp, “Life cycle assessment of hydrogen production via electrolysis – A review,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 85, pp. 151–163, 2014.

[4] Amar Toor, “https://www.theverge.com/2013/10/23/4946858/elon-musk-thinks-hydrogen-cars-are-bullshit,” theverge.com, 2013.

[5] M. Voldsund, K. Jordal, and R. Anantharaman, “Hydrogen production with CO2 capture,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 41, no. 9, pp. 4969–4992, 2016.

[6] Christina Benjaminsen, “https://www.sintef.no/en/latest-news/this-is-what-you-need-to-know-about-ccs-carbon-capture-and-storage/,” http://www.sintef.no, 2020.

[7] Wikipedia, “https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindenburg_disaster,” 2020.

[8] “https://www.aftenposten.no/okonomi/i/naVRr5/foreloepig-rapport-lekkasje-var-aarsaken-til-eksplosjon-paa-hydrogenstasjon-i-sandvika,” Aftenposten, 2019.

[9] Odd Roar Lange, “https://www.dagbladet.no/tema/cruiseverstingene-dropper-norske-fjordperler-etter-dette/71391279,” Dagbladet, 2020.