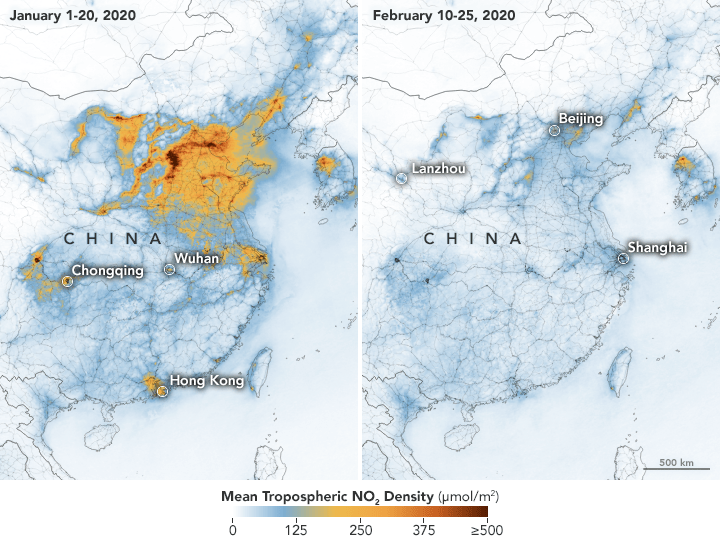

Bellow we see NO2 particles–a byproduct of industrial activity– in China before and after the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (Figure 1).

This image is quite striking, and it has, indeed, gone around the world.

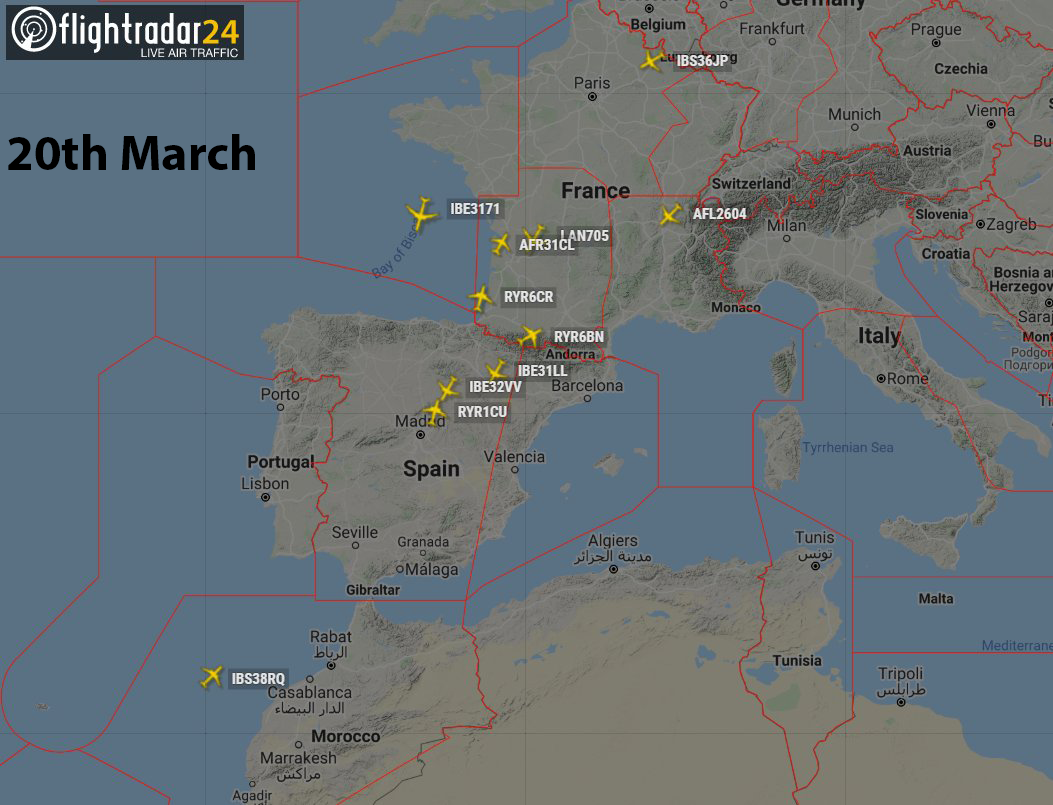

This not only shows the strength of a microscopic biological entity to partially halt the industrial and economic activity of a country such as China [1]–and, now, even world-wide (Figure 2); according to flightradar24 there are 43% less flights around the world compared to last year–but also brings up-front a less discussed climatic effect: the aerosols masking effect.

Figure 2. Flights coming in and out from Spain at 20.00pm on 13th March (left) and 20th March. Image modified from flightradar24.

Aerosols refer to a mix of particles suspended on air. They can be from natural or anthropogenic origin. Natural aerosols include volcanic eruptions, desert dust, fog, and others. Anthropogenic aerosols include haze and several industrial activity-derived pollutants; such as sulfates (SO2 ), nitrates (NO2), and others [2].

An interesting characteristic of aerosols is that they mostly cool our environment; by reflecting solar radiation and enhancing cloud-formation [3]. This effect was discovered by scientists in the early 90s [4]; their climatic models were predicting higher degrees of warming than what the real measurements showed–the answer turned out to be rather ironic: aerosols generated from industrial activity act, in fact, as climate coolers; thus, partially diminishing the end value of the complex climate warming equations.

Aerosols are short-lived–meaning they do not accumulate in the atmosphere and their effects have a short temporal window–contrary to CO2 which is long-lived, and its warming effect can last up to 200 years [5].

A study by Samset et al. modelled the global average temperature by removing the aerosol effect from the climate equation and simulating the drastic CO2 emissions reduction that would need to take place in order to reach the 1.5ºC climatic goal from the Paris Agreement.

The simulation by Samset showed that there would be an additional 0.7ºC global temperature rise in 100 years even when CO2 emissions were drastically halted. An increase in precipitations and extreme weather were also observed [6].

A more recent study simulated the effect of removing aerosols focusing on the alternative impact aerosols have in the atmosphere: reflecting sun radiation by its cloud formation ability [7]. They found that the aerosol cloud-mediated cooling effect was much larger than previous estimates. The authors concluded that their study adds up more uncertainty to past climate models as they did not effectively take into account the aerosol cloud-formation effect.

These two papers are interesting because they both focus on the two main aspects aerosols have on the environment. However, their results should be taken discretely as both of these studies work with these effects in an isolated manner and their conclusions concern those effects individually. A more informative study would be to integrate both climatic effects in the same simulations. This is, of course, quite challenging.

As we see the world greatly affected by the rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and, as a consequence, the countermeasures global leaders are implementing; being the halt in industrial activity and passenger mobility the most important–it will not be surprising to see CO2 emissions go down (even if it is a small fraction) together with aerosol emissions. The latter ones, having a paradoxical character: on one side improving our air quality, and on the other, losing (as long as industrial activity is down) the reflecting shield against sun radiation and its concomitant climate cooling protection.

GLS

[1] Gustavo Duch, “El virus del libre mercado,” http://www.ctxt.es, 2020.

[2] NASA, “Aerosols,” Earth Obs., 2020.

[3] R. J. Charlson and T. M. L. Wigley, “Sulfate aerosol and climatic change,” Sci.Am., vol. 270, no. 2, pp. 28–35, 1994.

[4] R. J. Charlson et al., “Climate forcing by anthropogenic aerosols,” Science (80-. )., vol. 255, no. 5043, pp. 423–430, 1992.

[5] IPCC, “Table 1: Examples of greenhouse gases that are affected by human activities.,” IPCC report. [Online]. Available: https://archive.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/wg1/016.htm.

[6] B. H. Samset et al., “Climate Impacts From a Removal of Anthropogenic Aerosol Emissions,” Geophys. Res. Lett., vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 1020–1029, 2018.

[7] D. Rosenfeld, Y. Zhu, M. Wang, Y. Zheng, T. Goren, and S. Yu, “Aerosol-driven droplet concentrations dominate coverage and water of oceanic low-level clouds,” Science (80-. )., vol. 363, no. 6427, 2019.