Dozens of climate scientists, energy experts, policy makers, ecologists, engineers, economists etc. gathered at the climate summit COP25 held in Madrid launched by the United Nations Climate Change initiative on December 2019 in order to find solutions to mitigate the anthropogenic climate change[1]–[4].

Recently, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) has released its provisional 2019 global climate report where it concludes that temperatures are on an increase rise since the1980s and that the past decade, 2010-2019, has been the warmest on record [5].

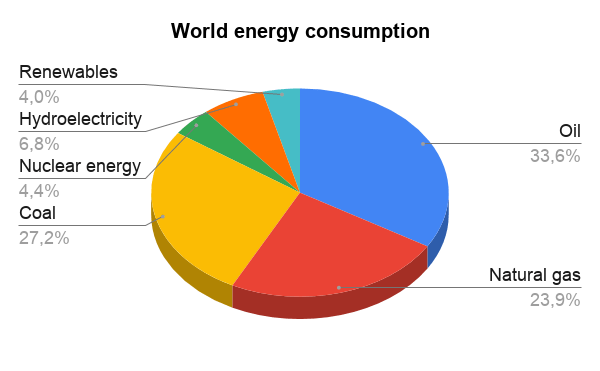

Since the 1850s, approximately, humans began using fossil fuels as their primary energy source to power their activities. Today, fossil fuels (coal, oil and gas) represent an 85% of the total global energy consumption (Fig. 1) [6]. The combustion of hydrocarbons releases CO2 into the atmosphere which results in the so-called green-house effect. The progressive accumulation of CO2 (and other green-house gases) in the atmosphere–today at approx. 410ppm [7]–is the main cause of the global temperature rise.

Therefore, a need for a shift towards other energy sources that do not release CO2 into the atmosphere is needed to mitigate and, ultimately, halt the impacts of climate change.

At the same time, live (both human as well as all others forms of live) is dependent on and takes place within a framework–the biosphere. Any human technological deployment will interact with the local surrounding and result in greater or lesser environmental impacts.

It is, thus, fundamental, to evaluate the environmental impacts a given technology will entail and carefully consider the relation between the gains it provides (energy produced) versus the inherent losses (environmental impact, pollution…).

Floating solar-panels emerge as a novel alternative technology in substitution of fossil fuels for energy production [8] yet little is known about the environmental impacts of this technology. The aim of this work is to serve as a critical starting point to set the stage for future studies assessing the environmental footprint of floating solar panels.

- Floating solar panels

Technology

Floating solar-panels are in essence the same as classical solar-panels with the difference of being located on a water body (mainly in inland water reservoirs) instead of on land.

Solar panels make use of the photovoltaic reaction where they generate electricity from sunlight; as no combustion reaction is involved in the generation of electricity and, thus, no CO2 is emitted, this technology belongs to the so-called clean energies.

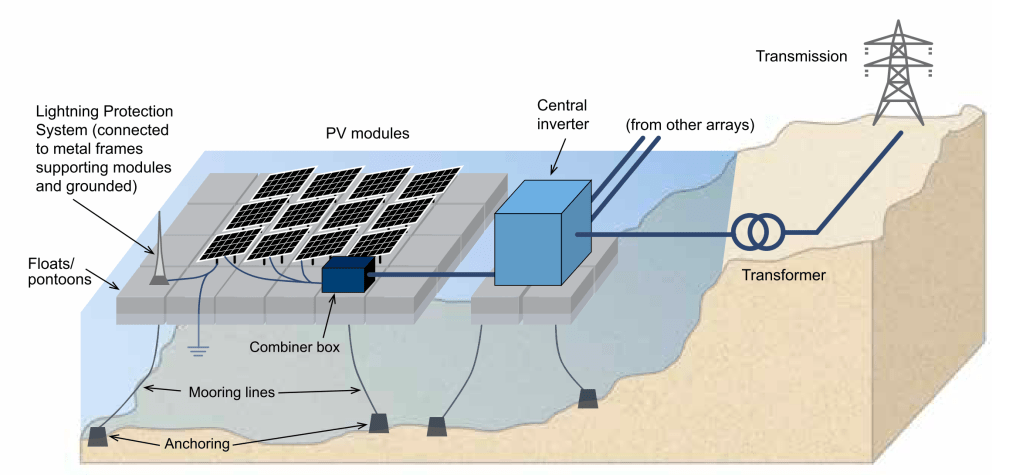

A typical floating photovoltaic (FPV) system consists of the photovoltaic panels and a central inverter mounted on floating platforms at the surface of a water body connected by cables to the anchoring points at the bed of the water body (Fig. 2).

Energy and scale

Over the recent years renewable energy such as solar and wind powered electrical generation have seen significant growth. Forecasts for the imminent years [9] continues as shown in Figure 3:

Two parameters need to be considered in order to understand the scale at which photovoltaic energy will be used; the potency we can obtain from a PV system and the surface area we will have to cover in order to achieve a specific potency.

By adopting an average land requirement factor of 0.0146 km2 /GWh/ year[1]–extracted from the IEA and other solar-energy companies–we can estimate the total land requirements (Fig.4) for fulfilling the envisioned solar PV electricity generation given in Figure 3. The 2030 projection indicates a land requirement of almost 50,000 km2; approximately corresponding to the combined surface areas of Catalonia and Valencia regions in Spain. This land requirement is also the driving force for introduction of floating solar. This is also, in part, the same driving force for the emergence of offshore wind generated power–another clean energy alternative.

As the above figure values indicate; large surface areas will have to be covered by solar panels if we want to substitute today’s global energy consumption by CO2-null energy production. In order to absorb the 10 TWh electricity generated by coal in 2018, for example, the surface requirement is expected to exceed 145,000 km2.

It is important to notice that to achieve this transition, a large deployment consisting of obtention of materials, assembling, transportation and final installation will have to take place and would probably be fuelled–at least at the early stages–by CO2-emitting combustibles.

- Effects on biodiversity/ecosystems

Based on the surface area estimations and the deployment magnitude needed to be covered by solar panels; we distinguish two scenarios of environmental impact: indirect and direct.

The assessment of the indirect environmental impacts is out of the scope of this work; we will, nevertheless, highlight them: these concern floating solar panel production; distinguishing the following phases: material extraction, components assembly and transport.

At the direct scenario we consider the environmental impacts that affect the deployment per se of this new technology. We have compiled the environmental impacts of the Da Mi Reservoir floating solar PV power plant at Vietnam [10] and compared them to those identified for offshore wind energy [11] (Table 1); including the following phases: construction/decommissioning and operational.

Despite of the lack of a large collection of supporting data, some conclusions can be inferred from floating-solar. Due to the intrinsic characteristics of this technology, floating solar is a less environmental-invasive technology compared to offshore wind farms: its structure consists of flat solar-panels floating at the surface of a water body, therefore, having a small interaction impact with the local environment; its anchoring to the bed of the water body is also minimal, as no large heavy structures need to be anchored to it; and its energy generation capacity is noise-free, as no turbines are involved.

Even though floating-solar does not require invasive environmental action–some environment impacts will take place and should be highlighted: at the construction phase, a degree of sediment dispersion and local habitat loss/dispersion is probable; spills of toxic substances should not be discarded as well as a possible entry source of invasive species.

At the operational phase, changes in the local aquatic community structure might take place. Another issue (not assessed in the Da Mi report) is the electromagnetic field generation from sub-water power cables; sub-water cables are known to require intimate contact with the bed of the water body and the electromagnetic field emanated from those might interfere with the local organic communities [12].

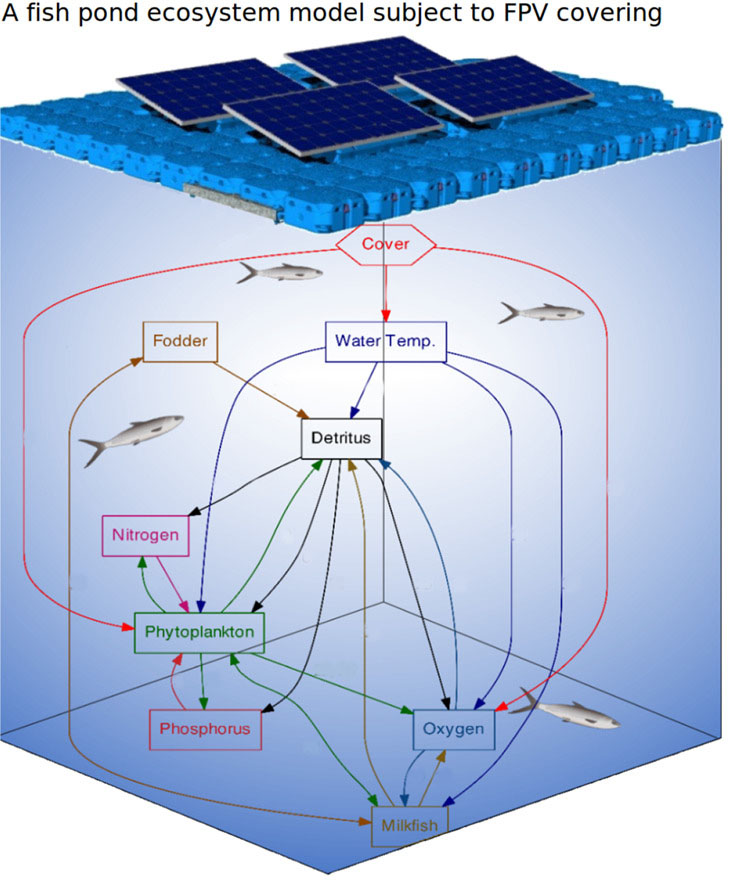

Two important environmental factors that specifically concern floating-solar technology are the sunlight and gas-exchange blocking effects a large deployment of floating solar-arrays will pose to the aquatic ecosystem.

Light is essential for photosynthesis in plants and it is a cue for daily and seasonal physiological rhythms for both plants and animals [13]. Furthermore, light is a key factor on the sustainability of food webs as it constitutes the primary energy source for autotroph organisms–which are at the base of the trophic chain. Additionally, sunlight influences the water temperature which is, in turn, another important factor of an aquatic ecosystem [14].

Gas exchange (oxygen, carbon-dioxide, water evaporation and other volatile components) takes place between the water-air interphase and constitutes another important factor for the maintenance of aquatic ecosystems [14]. Oxygen, for example, is an indispensable requirement for all aerobic organisms (which are the majority of freshwater species) and its intake comes from diffusion from the atmosphere and release by photosynthetic organisms. Carbon dioxide, together with light, are important components for photosynthesis.

- Discussion and conclusion

The two reviewed reports show mainly minor impacts to the aquatic ecosystem (with a few moderate exceptions) for both offshore wind and floating solar. Despite of their environmental assessments being mostly correct and floating solar showing minor effects than offshore wind; an important remark should be made: the small environmental impact of these technologies is largely dependent on the magnitude dimension of the project. That is, minor environmental impacts can be achieved as long as these installations remain relatively small in size in relation to the ecological system they will be part of.

A limiting issue that these two reports–and other studies on the environmental viability of floating solar [15]–show is the lack of proper estimations on the cumulative effects minor environmental issues will pose on the environment over long periods of time.

For example, in their study, Château et al. performed a mathematical analysis where they compared different FPV coverage–20%, 40% and 60%–and assessed the ecosystem change. According to their mathematical model, they conclude that it is possible to cover up to 60% of the water body and still maintain a 70% of fish production [15]. However, it is important to notice that they calibrated their computational model using experimental data from a pond with no cover and a pond with a 40% cover in southern Taiwan. Importantly, and as aforementioned, their experimental collection data was done over the period of one year.

Ecosystems are the sum of multiple factors–greater than the ones highlighted here– that show complex relations impacting each other which, in turn, contribute to the maintenance of a stable ecosystem. Changes in one of these factors (Fig.5) might alter, in the long-term, the ecological state of an aquatic ecosystem into a different one. It is within a specific ecological state that humans (as well as other animals) have evolved on Earth between 300.000 [16] and 6.000 years (according to other sources [17]) ago. Therefore, robust environmental monitoring and assessment of the long-term effects floating-solar poses on aquatic ecosystems should be undertaken.

- References

[1] S. Arrhenius, “In the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground,” Philos. Mag. J. Sci., 1896.

[2] H. E. S. Roger Revelle, “Carbon Dioxide Exchange Between Atmosphere and Ocean and the Question of an Increase of Atmospheric CO2 during the Past Decades,” Tellus, 1957.

[3] “United Nations Conference on the Human Environment – Stockholm declaration,” 1972. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_Conference_on_the_Human_Environment.

[4] C. Rosenzweig et al., “Attributing physical and biological impacts to anthropogenic climate change,” Nature, vol. 453, no. 7193, pp. 353–357, 2008.

[5] W. M. Organization, WMO provisional Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2019, vol. 1961, no. September. 2019.

[6] D. Spencer, “BP Statistical Review of World Energy Statistical Review of World,” Ed. BP Stat. Rev. World Energy, pp. 1–69, 2019.

[7] and H. A. M. C. D. Keeling, S. C. Piper, R. B. Bacastow, M. Wahlen, T. P. Whorf, M. Heimann, “The Keeling Curve,” 2019.

[8] SERIS, “Where Sun Meets Water – Floating solar market,” Where Sun Meets Water, 2018.

[9] IEA, “Tracking Power,” 2019.

[10] Asian Development Bank, “Initial Environmental and Social Examination Report: Da Mi Hydro Power Joint Stock Company Floating Solar Energy Project,” Report, no. October, 2018.

[11] D. Wilhelmsson et al., Greening Blue Energy: Identifying and managing the biodiversity risks and opportunities of offshore renewable energy. 2010.

[12] M. S. Bevelhimer, G. F. Cada, A. M. Fortner, P. E. Schweizer, and K. Riemer, “Behavioral responses of representative freshwater fish species to electromagnetic fields,” Trans. Am. Fish. Soc., vol. 142, no. 3, pp. 802–813, 2013.

[13] C. J. Krebs, “Ecology. The Experimental Analysis of Distribution and Abundance,” Q. Rev. Biol., 1973.

[14] C. Brönmark and L. A. Hansson, The biology of lakes and ponds. 2017.

[15] P. A. Château, R. F. Wunderlich, T. W. Wang, H. T. Lai, C. C. Chen, and F. J. Chang, “Mathematical modeling suggests high potential for the deployment of floating photovoltaic on fish ponds,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 687, pp. 654–666, 2019.

[16] E. Callaway, “Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species’ history,” Nature, 2017.[17] The Bible, The Book of Genesis.

[17] The Bible, The Book of Genesis.

[1] This value represents the average total land requirement per annually GWh produced electricity for solar PV plants in the US [2].

Very interesting.

Can I suggest you the issue of waste management and its effect on the environment or on health? … Surely you get a lot of juice

LikeLike

Hi,

Thanks for your comment! Indeed, waste management is another really interesting issue to explore together with the associated impacts on health/environment. Thanks for that. I’ll definitely keep this in mind for future posts! : )

G

LikeLike

Floating-solar photovoltaic energy has huge areas to operate so environmental effects can be minimised. Thank you 😊

LikeLike